-

Αναρτήσεις

16254 -

Εντάχθηκε

-

Τελευταία επίσκεψη

-

Ημέρες που κέρδισε

26

Τύπος περιεχομένου

Forum

Λήψεις

Ιστολόγια

Αστροημερολόγιο

Άρθρα

Αστροφωτογραφίες

Store

Αγγελίες

Όλα αναρτήθηκαν από kkokkolis

-

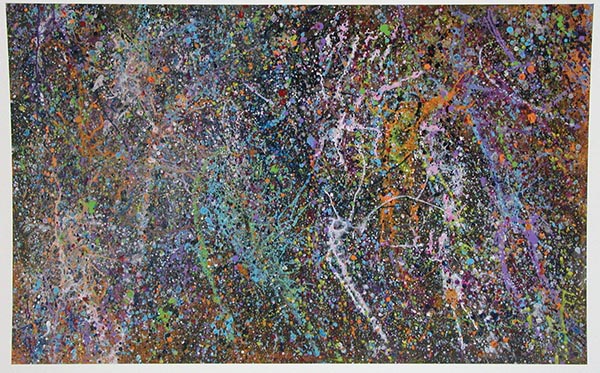

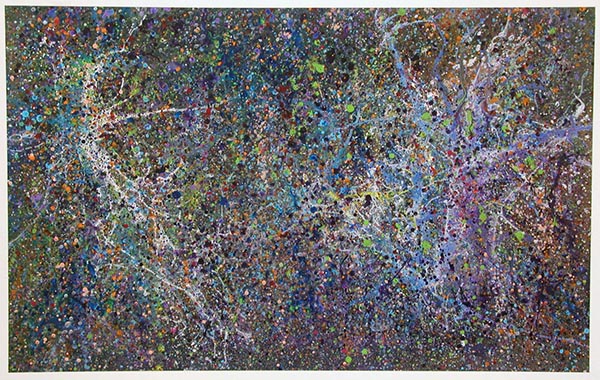

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

The Firefly Encyclopedia of astronomy, Paul Murdin - Margaret Penston, 2004 Το αγόρασα σήμερα το πρωί και το βρίσκω ενδιαφέρον. Καλό βιβλίο αναφοράς αν και θα επιθυμούσα μια περισσότερο πρόσφατη έκδοση. http://www.protoporia.gr/product_info.php/products_id/312864

-

Χαρίζεται THE MONTHLY SKY GUIDE Β' Έκδοση

kkokkolis δημοσίευσε μια συζήτηση σε Μικρές Αγγελίες - Αρχείο

Χαρίζεται το βιβλίο THE MONTHLY SKY GUIDE - Οδηγός παρατήρησης του ουρανού ανά μήνα, Β' Έκδοση 2007-2011. Η προσφορά προορίζεται για αρχάριο νεεότερο των 23 ετών, χωρίς τηλεσκόπιο ή με έως 90mm αχρωματικό ή 130mm Νευτώνιο, ο οποίος μπορεί να το παραλάβει χέρι με χέρι κάπου στον Πειραιά. -

Ρύθμιση από πρωτάρη

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της gka σε Η γωνιά των νέων αστροπαρατηρητών

Κατάστημα αυτό: http://www.astronomy.gr/ Χρειάζεσαι κάτι ελαφρύ, λόγω πλαστικού εστιαστή και μεγάλου μήκους. Στην θεωρία μπορείς να πας έως 140x, η γνώμη μου είναι όμως να στοχεύσεις στα 100x, δηλαδή μέχρι 7mm. Μια οικονομική λύση είναι ο Skywatcher Zoom 21-7: http://www.astronomy.gr/main.cfm?module=eshop&action=detail&id=812 Είναι ελαφρύς, καλύτερος από τους φακούς της Bresser και καλύπτει όλο το φάσμα χρήσιμων μεγεθύνσεων του τηλεσκοπίου, χωρίς να χρειάζεσαι Barlow. Τον είχα κάποτε. Μπορείς να τον πάρεις περίπου 30 ευρώ μεταχειρισμένο αν βάλεις αγγελία. Σε παρόμοια τιμή ή μικρότερη αγοράζεις και έναν Plossl 32 ή 25mm, επειδή ο Zoom έχει στενό πεδίο στα 21mm. Με δύο φακούς είσαι εντάξει. Οτιδήποτε ακριβότερο δεν θα αξιοποιηθεί στο Bresser, θα είναι απίθανο να δεις διαφορά και το βάρος θα σε δθυσκολέψει. Ακόμη φθηνότερη λύση είναι να πάρεις από κάποιον τα Super Plossl 25 και 10mm της Skywatcer. Συνοδεύουν πολλά τηλεσκόπια και περισσεύουν από πολλούς. Και ακόμη φθηνότερη τα Kellner Modified Achromat 25 και 10 της Skywatcher. Ακόμη και αυτά είναι καλύτερα από τα Huygens της Bresser. 20- 30 ευρώ φθάνουν και για τα δύο μαζί και πολλά λέω. Αλλά ο 21-7 έχει καλύτερο eye relief μακράν στις μεγάλες μεγεθύνσεις. Καλύτερη λύση κάποιοι φακοί ευρέως πεδίου από το εξωτερικό: Agena SWA 72 μοιρών 20 & 15mm με έναν Barllow 2x ή Agena EWA 66 μοιρών 9 & 6mm. Καλή ποιότητα, μεγάλο πεδίο, αχτύπητες τιμές αλλά σπάνιοι στην Ελλάδα (πουλήθηκαν κάποιοι προ μηνός στις αγγελίες). Τέλος, αν θέλεις κάτι να σου μείνει και μετά, ο Celestron Zoom 24-8 είναι καλή λύση. Κοστίζει βέβαια περισσότερο από ολόκληρο το Bresser, αλλά ίσως τον βρεις μεταχειρισμένο και αυτόν περί τα 60 ευρώ. Φυσικά τις τιμές των μεταχειρισμένων καθορίζει ο πωλητής και όχι εγώ. Ενδεικτικά τις αναφέρω. Μπερδεύτηκες; Πάρε τον χρόνο σου και βρες οικονομικές λύσεις που να ταιριάζουν στον χαρακτήρα του Bresser 70/700. Σπεύδε βραδέως. -

Ρύθμιση από πρωτάρη

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της gka σε Η γωνιά των νέων αστροπαρατηρητών

Κώστα, έχω την ίδια ακριβώς βάση και σε διαβεβαιώνω πως είναι ευκολότερο να την χρησιμοποιήσεις υψαζιμουθιακά. Στηρίζεται καλύτερα και το τηλεσκόπιο επειδή το κέντρο βάρους περνά από το τρίγωνο των σκελών του τρίποδα. Θα συνηθίσεις σύντομα τους δυο μοχλούς. Ο ερευνητής και οι φακοί είναι πολύ κακής ποιότητας. Μπορείς ωστόσο να χρησιμοποιήσεις τους 2 μεγαλύτερους και να ξεχάσεις τον 4mm. 2 Plossl ή φθηνοί και ελαφρείς SWA θα σε βοηθήσουν αργότερα. Μπορείς να προσθέσεις κάποιο βάρος στον τρίποδα για ευστάθεια. Δες στην φωτογραφία: ένα πολύ βαρύτερο τηλεσκόπιο με βαρύτερο διαγώνιο και φακό πάνω στην βάση και μεγάλες μεγεθύνσεις γίνονται εφικτές χάρη στα βάρη. Κουνάει φυσικά λίγο αλλά σταθεροποιείται σε λίγα δευτερόλεπτα. -

Ιδέες & προτάσεις για αγορά ενός καλού Ερευνητή

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της Bi2L σε Λοιπά θέματα αστρονομικού εξοπλισμού

Αυτό είναι το ίδιο τηλεσκόπιο με το Orion ST80, με τα χρώματα της Skywatcher. Η βάση είναι για κλάματα, καλύτερα να το αγοράσει κάποιος σαν απλό σωλήνα. Σχετικά με τους αυθεντικούς ερευνητές οι Stellarvue είναι εξαιρετικοί. Χρησιμοποιούσα τον F50 σαν διόπτρα αρκετόν καιρό και τώρα που τον έβαλα κάπως ημιμόνιμα πάνω στο Nexstar μου λείπει. Ένας Stellarvue 80 με Panoptic 24 είναι όνειρο και χρώμα δεν θα δεις αφού δεν θα στοχεύεις τους πλανήτες. Αλλά δεν προορίζεται για φωτογράφιση. Τώρα αν δώσει κάποιος 1000 ευρώ για ερευνητή θα μπορούσε να πάρει ArgoNavis, έτσι δεν είναι; Και ένα Tak πάνω σε Dob στην υγρασία της Κέρκυρας δεν θα σε αφήνει να είσαι χαλαρός. -

Ιδέες & προτάσεις για αγορά ενός καλού Ερευνητή

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της Bi2L σε Λοιπά θέματα αστρονομικού εξοπλισμού

Stellarvue F50, F60 ή F80. Άψογο είδωλο. Αν και στα 80mm δεν βλέπω τον λόγο να μην πάρεις ένα Orion ST 80/400 που είναι και φθηνότερο. Δεν χρειάζεσαι αποχρωματικό για ερευνητή. -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

1 έτος Σύμπαν της Τέχνης! Περισσότερες από 5500 δημοσιεύσεις Σχεδόν 90000 αναγνώσεις Ένας σειρηνικός εθισμός Μια φλογισμένη εμμονή Ένα διαθεματικό μυστήριο Κατακλύζομαι από ένα όργιο συναισθημάτων, αντιφατικών και αμφίσημων. Όλα όμως τα διαποτίζει ικανοποίηση και όλων κυριαρχεί η χαρά. Ευχαριστώ όλους όσους συμμετείχαν με περισσότερες από 500 συνολικά δημοσιεύσεις Ευχαριστώ όσους το σπούδασαν Ευχαριστώ όσους το δέχθηκαν ή και το ανέχθηκαν Επιτρέψτε μου να το γιορτάσω με 2 έργα τέχνης, ένα εκτός και ένα εντός θέματος και μην με ρωτάτε ποιο είναι ποιό... Une Charogne, Fleurs du mal, Charles Baudelaire, 1857 Rappelez-vous l'objet que nous vîmes, mon âme, Ce beau matin d'été si doux: Au détour d'un sentier une charogne infâme Sur un lit semé de cailloux, Les jambes en l'air, comme une femme lubrique, Brûlante et suant les poisons, Ouvrait d'une façon nonchalante et cynique Son ventre plein d'exhalaisons. Le soleil rayonnait sur cette pourriture, Comme afin de la cuire à point, Et de rendre au centuple à la grande Nature Tout ce qu'ensemble elle avait joint; Et le ciel regardait la carcasse superbe Comme une fleur s'épanouir. La puanteur était si forte, que sur l'herbe Vous crûtes vous évanouir. Les mouches bourdonnaient sur ce ventre putride, D'où sortaient de noirs bataillons De larves, qui coulaient comme un épais liquide Le long de ces vivants haillons. Tout cela descendait, montait comme une vague Ou s'élançait en pétillant; On eût dit que le corps, enflé d'un souffle vague, Vivait en se multipliant. Et ce monde rendait une étrange musique, Comme l'eau courante et le vent, Ou le grain qu'un vanneur d'un mouvement rythmique Agite et tourne dans son van. Les formes s'effaçaient et n'étaient plus qu'un rêve, Une ébauche lente à venir Sur la toile oubliée, et que l'artiste achève Seulement par le souvenir. Derrière les rochers une chienne inquiète Nous regardait d'un oeil fâché, Epiant le moment de reprendre au squelette Le morceau qu'elle avait lâché. — Et pourtant vous serez semblable à cette ordure, À cette horrible infection, Etoile de mes yeux, soleil de ma nature, Vous, mon ange et ma passion! Oui! telle vous serez, ô la reine des grâces, Apres les derniers sacrements, Quand vous irez, sous l'herbe et les floraisons grasses, Moisir parmi les ossements. Alors, ô ma beauté! dites à la vermine Qui vous mangera de baisers, Que j'ai gardé la forme et l'essence divine De mes amours décomposés! To ψοφίμι, Τα άνθη του κακού, Κάρολος Μπωντλαίρ, 1857 Μετάφραση: Άγγελος Σημηριώτης Θυμάσαι φως μου, εκείνο που αντικρίσαμε κάποιο καλοκαιριάτικο πρωί τόσο γλυκό; Σ' ενός μονοπατιού το στρίψιμο κειτότανε ένα ψοφίμι στα χαλίκια φριχτό! Με πόδια σηκωμένα σαν γυναίκα ακόλαστη, που φλόγα και φαρμάκια ο ίδρως της ξερνά, άνοιγε την κοιλιά του την δυσώδικη, νωχελικά και κυνικά εκεί - δα! Ο ήλιος πάνω στη σαπίλα αυτή αχτιδόλαμπε για να την ψήσει όσο μπορούσε πιο πολύ, να ξαναδώσει στη μεγάλη φύση τρίδιπλα, ό,τι είχε μια φορά συνθέσει αυτή. Κι ο ουρανός κοιτούσε το λαμπρό το σκέλεθρο σα λουλουδιού μια ολάνοιχτη καρδιά. κι ήτανε τόση η δυσωδία, που 'νιωθες να σου 'ρχεται στα χόρτα σα λιγοθυμιά. Πάνω στη σάπια αυτή κοιλιά οι μύγες βούιζαν, κι έβγαινε από κει μέσα μαύρη, η στρατιά των σκουλικιών που σα λασπόνερο έτρεχε, στα σάρκινα κουρέλια της, τα ζωντανά. Κι όλ' αυτά ανέβαιναν, σαν κύμα και κατέβαιναν, πετούσανε σα σπίθες λαμπερές και το ψοφίμι φουσκωμένο, λες, απ' άυλο φύσημα, εζούσε σε μυριάδες τώρα δα ζωές. Ζωές που ξέχυναν μια μουσική παράξενη, σαν του νερού που τρέχει και του αγέρα τη φωνή, ή σαν του σιταριού που ρυθμικά στο λιχνιστήρι του το γυροφέρνει ο λυχνιστής και το κουνεί. Κι οι φόρμες σβήναν, μοιάζαν πια σαν όνειρο, σα σχέδιο που ο καλλιτέχνης αρχινά, και το ξεχνάει στο τελάρο μισοτέλειωτο, αποτελειώνοντάς το μες το νου του μοναχά. Πίσω απ' τα βράχια, κάποια σκύλα ανήσυχη μας κοίταζε με μάτι όλο θυμό, παραμονεύοντας να ξαναπάρει από το σκέλεθρο, το κόκκαλο που άφησε πάνω στο φευγιό. Κι όμως θα γίνεις σαν και το ψοφίμι αυτό το απαίσιο, σαν τη σαπίλα τούτη τη φριχτή, αστέρι των ματιών μου κι ήλιε, εσύ, της πλάσης μου, εσύ άγγελέ μου, αγάπη μου τρελή. Ναι, τέτοια θα γενείς, στις χάρες, εσύ ρήγισσα όταν την ύστερη πνοή θ' αφήσεις της ζωής, και πας κάτω απ' τα χόρτα, απ' την παχιά την άνθηση για να σαπίσεις πλάι στους σκελετούς της γης! Πες στο σκουλίκι τότε, ωραία μου, που θα σε τρώει με φιλιά, πως στην καρδιά, τη φόρμα και τη θεία ουσία φύλαξα, του έρωτά μου του αποσυνθεμένου πια! The Sombrero Galaxy from Hubble Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI / AURA) APOD 15/05/11 -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

A Sunset, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1772-1834 Upon the mountain's edge with light touch resting, There a brief while the globe of splendour sits And seems a creature of the earth, but soon, More changeful than the Moon, To wane fantastic his great orb submits, Or cone or mow of fire : till sinking slowly Even to a star at length he lessons wholly. Abrupt, as Spirits vanish, he is sunk ! A soul-like breeze possesses all the wood. The boughs, the sprays have stood As motionless as stands the ancient trunk ! But every leaf through all the forest flutters, And deep the cavern of the fountain mutters. -

Το μέλλον των διαστημικών αποστολών - Ψηφοφορία!

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της Tsaprazi σε Διάστημα

Κατά βούληση. -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

Κύπελλο Di Lorenzo, Antonia di Lorenzo, 2010 Πορσελάνη με σμάλτο σε Βενετσιάνικο στυλ του 15ου αιώνα INVENTAS VITAM IUVAT ECOLUISSE PER ARTES, Βιργίλιος -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

Tales of Astronomy Ι, Ed Ting, 2003 It all started one cold January morning during a prolonged stretch of dreary, cloudy weather. Our local observing group had been caught in a classic New England Catch-22: when the temperatures were warm enough to go observing, it was always cloudy out. On the other hand, when the skies cleared, the temperatures dropped to the single-digits or below. I had just been elected President of our local astronomy club, and there were duties to perform. A stack of papers by my desk was slowly getting taller; I would have to get down to business soon. Naturally, the makes the avid observer a little stir crazy. I had spent the morning wandering in and out of the garage, solemnly inspecting my telescopes the way a drill sergeant might look over a row of cadets before bedtime. A place for everything, and everything in its place. My scopes were quietly lined up like soldiers against the back wall, waiting to do battle against the night sky. The Takahashi FS102 4" refractor was on the far left, followed by the 6" Dobsonian, the 8" SCT, and the 10" Starmaster. On the far right lay the big gun: a 20" Obsession on a strong platform with lockable castors underneath. All lay dormant, with cloths carefully draped over them to protect the delicate optics. On shelves in between the scopes lay dedicated eyepiece cases for each scope. The Tak's case contained nothing but imported high-quality orthoscopics, each of which cost more than most beginner's telescopes. Some of them took months to obtain from overseas suppliers. The 6" and 8" scopes had generic Kellners and Plossls for star party use. The Starmaster's case consisted of expensive Plossls and Naglers, while the case for the big Obsession (a watertight aluminum flight case) sported nothing but long focal length Panoptics and Type 4 Naglers, some of them in duplicate. Later, I was sitting at my desk slogging through the stack of club business. Pete Kip, former President and current Treasurer, had given me instructions on what he thought should be done. He was also emailing me asking me why I hadn't acted upon his suggestions. I was getting the nagging feeling deep down that Pete still felt he was the President of the club. I reading a stack of old astronomy magazines when the phone rang. It was an observing buddy we often refer to as "Old Dan." "Ed, it's Dan. I think I'm going to sell the Traveler." I sat up. Understand, amongst our group, a statement like "I am going to sell the Traveler" was likely to have the same effect on us as the statement "Pamela Anderson is now single" could have among unattached men in Hollywood. I mean, the implications were huge. "Why didn't you tell me this two months ago?" I had just bought the Takahashi because I was sick of being on AP's waiting list. "Well," said Old Dan, "I was still working on my double star list and wanted to see how many I could split with a small refractor. That observing project is done. Now it's time to move on." "How much do you want for it?" I took out my checkbook and winced at the painfully low balance. "Well, you're a friend, and if you bought it I know the scope would still be local and in good hands." Old Dan often used these statements to soften me up when he really wanted to move in for the kill. He knew I wanted the Traveler. Perhaps it was my panting on the phone that gave it away. Old Dan quoted me a price. I leapt off my chair. "For the optical tube alone? I could buy TWO Takahashis for that!!" "Yes," said Old Dan, calmly. "But I've been checking prices and I could still make more on Astromart or ebay. This price is really very reasonable when you get down to it. In a way, I'm actually losing money." Dan is an accountant by trade, and he has a way of smoothly saying things like this that make you believe him. I looked again at my checkbook statement. There was no way this could be done with the cash I had on hand. If I tried to write a check for the stated amount, my checkbook would probably implode from the financial stress. "Is there anything else I can give you to make up the difference?" "Well, now that you mention it," Old Dan was very skilled at making me think these ideas are my own. I was a fish being played by a master fisherman, and we both knew it. "I've always liked that Starmaster of yours. You know - the one with the Zambuto mirror. Good stuff." We worked out the terms. The amount is not important. Suffice it to say, I still needed to come up with cash to get that Traveler. As soon as I hung up with Old Dan, I called my friend Mike. His wife answered the phone. She sounded a little stressed out. "He's not here right now. He went to Ron's Telescope Treasures for the morning. I'm alone with the babies. I gotta go. Can you call back?" I called Ron's. "Ron's Telescope Treasures! How can I help?" "Hi Ron, is Mike there?" I hear shuffling noises. Then in a muffled tone in the background I hear, "Mike, Ed's on the phone for you! And don't tie up this line too long!" More shuffling noises. Then Mike came on the phone. "Hey Ed, they just took in a used C14 in trade here!" My heart sank. I was hoping to sell him one of my scopes. If he was looking hard at that C14, I might lose the Traveler. "Mike, Dan is thinking of selling the Traveler." Silence at the other end of the line. "Don't even think about it. I have first dibs. But I need some cash. I know you've been looking at my Takahashi for some time now. I don't need two 4" refractors. What if I gave you a great deal on it?" "Yeah...that's a nice scope" said Mike. But I could hear hesitation on his end. "But... the truth is, I've almost reached a deal with Ron on this C14. I'm trading in three scopes and making payments on the rest. If I take out another loan on a scope, my wife will kill me. Truth be told, I'd rather have your Takahashi, but the C14 will do nicely for now. I just don't have the money." Now it was my turn to be silent. I was so close to getting that Traveler, and now it was slipping away. I thought about selling the Tak to Ron, but I'd be giving it away. I could use Astromart or ebay, but neither of these outlets gives you cash fast enough. I needed money, now. Then, an idea hit. "Mike, put Ron on the phone." I asked Ron how much he wanted for the C14. The price was low. Not low as in "That's a nice deal" but low as in "This price is just way too low for any sane human being to pass up. The Laws of Civilization demand that you buy it." Ron said he knew the price was good, but he's nervous about holding on to big telescopes. They take up too much space and too many dollars, and wives don't like them. He'd rather move it at a low margin than keep it for a long time, hoping someone will come along and pay top dollar. Now I was in a double quandary. I wanted the Traveler, but the C14 was such a good deal, I wanted it, too. "Mike, I've got an idea. You said you'd prefer the Takahashi over the C14, right?" "Right." "Okay, here's my plan. I'll trade in the Takahashi and some other scopes for the C14. If I work this right, Ron will actually be paying me money back. Plus, he'll get some smaller inventory that's easier to move. You can buy the Tak back from Ron at a low profit margin. Then I take the cash and the Starmaster and trade it to Old Dan for the Traveler and we're all happy." "...but..." "You'll still get use of the C14 - heck, we only live four miles apart. I'll give you the spare garage door opener so you can come over any time you want." Of course, I didn't tell Mike everything. What I didn't tell him was that I planned to sell the C14 in a few months. The price was so low, I could easily make money back on it to buy some of my stuff back from Ron's. In this way, I was using Ron's as a low-rent astronomical pawn shop. The way I saw it, I wasn't selling him my stuff, I was just letting him hold on to it for a short time. Yes, this was working out beautifully. Mike was still on the phone. I heard the other line ring into the shop. Ron answered. "Mike, how does this sound?" "Well.." said Mike. "To tell you the truth, I was thinking about using the C14 for a while and then selling it. The price is really good, you know." Gulp. "Uh, yes, I know." Mike was thinking the same thing I was thinking. Then, Ron came on the line. "Hey guys -- it's Dan on the other line. I'm sorry, Mike but I told him about the C14 last night. He wanted the first right of refusal on it. But since I hadn't heard from him as of this morning, I figured it was for sale to you. But now Dan says he wants it. I'm patching you all in so you can talk to each other." Now it was all coming together. Old Dan was selling the Traveler to me to get the C14. Then he was probably planning to sell it to someone else and make some money. With all three of us staking a claim on the C14, we seemed to be at an impasse. But I was in too deep at this point to give up. I came up with a solution. We form a temporary "corporation." The corporation buys the C14, and we rotate the scope from house to house over time. After a while, by majority vote, we sell the scope and split the profits. In a way, this was even better than my original plan, since I only had to come up with 1/3 of the money to get my share of the C14 (which I could easily do by trading in the 6" Dob and the 8" SCT.) This was going to work out after all. I was getting Old Dan's Traveler, Mike was getting my Takahashi, Dan was getting my Starmaster, Ron was getting my 6" and 8" scopes, and we were all buying the C14 together. What could be simpler? "In fact," said Old Dan, "you can even put the ad on Astromart right now: FS In Three Months, like-new C14." "Sounds good to me," said Mike. "We're selling a scope we don't even own yet?" I asked. "We'll all make money on it," said Mike. "Agreed," said Dan. "OK, I'll do it right now," I said. I have two phone lines in the house, so I logged on and placed the ad. "Done," I announced a few minutes later. Mike spoke next. "Ron says if you and Dan come down here this morning with your scopes we can do the deal right now." "All right," I said. "I'll pack up the car as soon as we hang up." "I'll be there, too," said Dan. I was getting ready to hang up when the "You've Got Mail" icon flashed on my screen. "Hold on, guys." It was a response to the ad, which had been up for less than 5 minutes. I read the ad. "OK guys, here the deal. Someone named Frank in California says he'll buy the C14 and pay the shipping, too. But he wants the scope this week." "But if we sell it now - " said Dan. Mike finished the sentence for him. "- we won't get to look through it at all." "Yes," I said, "But do you know what the shipping cost is on a big scope like this?" A few moments of silence while we all pondered this. "I say we sell it," said Dan, breaking the ice. "Me too," said Mike. "I guess the majority has spoken," I said. "We can just have Ron ship out the C14 from his shop today. No need having us even taking the scope home at this point." "I'm responding to Frank as I speak," I said, typing as I talked. As I gave out my mailing information to Frank, another e-mail popped up. "It's from a guy in Texas who wants the C14 and wants to know if we'll take a 16 inch Starfinder, two Chinese achromats, and first right of refusal on a 7 inch Mak-Newt for it. I guess I better delete the ad, eh?" I did. It was nice to make a modest profit for three people for only a few minutes' work. But I still had to get down to Ron's and give him the Tak, the 6" and the 8" to settle up so that I could get Dan's Traveler. And Dan had to get down to Ron's with his share of the soon-to-be-departed C14, and the Traveler to give to me. I found myself loading up the car with all the scopes I owned except the 20" Obsession, which watched over me like a giant, quiet sentinel as I carted away all of its brethren for good. The scopes barely fit inside the car, but with some creative packing, I managed. When I arrived at the shop a few minutes later, Dan was already there. When I handed the Takahashi over to Ron, he passed it on to Mike, who immediately gave it to Dan. Dan smiled. "I just bought your Takahashi from Mike," he said. "WHAT?!?" "We talked while you were on your way over here," said Mike. He doesn't have a 4 inch refractor anymore, since you're buying the Traveler. So he offered me a good price on it and I'm taking the money. You never know what's going to show up at the shop that I might want." I shook my head to clear my mind. This was getting hard to follow. I did my deal with Ron and handed over the money to Old Dan. It felt funny - essentially, I was giving a huge pile of cash AND the Takahashi to Dan for the Traveler. I looked over at Dan, cradling his new Takahashi. It had gone from me to Ron to Mike to Dan - four owners - in less than thirty seconds. In any case, I got what I wanted - the Traveler. But I saw Mike looking my way. "You know," he said, "I just made a pile of cash from the sale of the C14 and the Tak. Plus, I came down here with more than enough money to buy the C14 to begin with. So what if I offered you THIS -" He fanned out a spread of $100 bills in his hand, looking like the world's richest magician. It was entrancing, seeing all that cash. I left like the John Travolta character in Pulp Fiction when he opened up the suitcase. Golden filtered light seemed to shine into my eyes from all that money. " - for that Traveler?" As if in a daze, I saw myself handing the Traveler to Mike, in exchange for the money. Now Dan and Mike were both smiling. Mike had the Traveler, and Dan had the Takahashi and my Starmaster. I, on the other hand, had nothing. "I don't have any telescopes left," I said. "You have the Obsession," said Dan. "Yeah, but - but -" "See you, Ron!" said Mike, waving. "See you guys later!" said Dan as he left the store. Sometime later that afternoon, I stood in my garage, wondering what had happened. It was a lot quieter in there now, with the 20" Obsession the only survivor from the fray that morning. Four shelves with lonely-looking eyepiece cases hung from the walls. As I stood there, sulking, I plunged my hands into my pockets, and pulled out a huge wad of something. It was a pile of cash, thousands of dollars worth, in small bills. I wandered inside the house and looked at the pile of club business to be done. I had to upload next year's club calendar, for one thing. I sat at my computer, and logged on. There were a bunch of messages from Pete Kip. Instead of reading them, I hit the familiar tab on my "favorites" folder. Through the flickering lights on the screen, I waited until the latest classified ads came up, and started reading. The first ad read, "Telescope For Sale..." -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

Tales of Astronomy Ι, Ed Ting, 2002 "This wine is a little dry," said Kip. "I didn't realize you cared," replied Ron. An uneasy silence fell between the two men. Pete Kip and I were having dinner at Ron's place. It was a meeting among some of the officers in our astronomy club - Kip was the club's past President and current Treasurer, while Ron's term at the helm was expiring next month. Both of them had mentioned me as a possible future President and they asked me to sit in at dinner. But all talk of club leadership ended very early in the evening, as the two men did not easily get along. Ron and Kip were polar opposites. Pete Kip, a tall, lanky, athletic, perpetually tanned middle-aged man, had led the club through two productive but highly tumultuous years. Highly organized (it was rumored that he needed a Day Timer just to organize his Day Timer), he spoke with authority. Unfortunately, he was also quick to offend. Once, at an officer's meeting he flew into a rage because he disagreed with the way the newsletters were being folded. After two years he had the astronomy club running like a top but no one in it was happy. His favorite way to begin a sentence was with the words, "You should." Ron was elected President in a landslide when Kip sought a third term. He was a short, stocky man with a long, unkempt hair. Disheveled, even sloppy, Ron was apt to forget dates, club events, and (once) a club meeting (the Vice President ran the meeting that day.) While everyone loved him, it was obvious that after only a few short months, his disorganized style had left the club in shambles. Club events came and went without any notice. The club's web calendar had not been updated in months. We missed participating in the club's Astronomy Day at the for the first time ever, which infuriated Kip. At a recent meeting, he stood up and made an uncomfortable speech to the members about how incompetent he thought Ron was, and this was the beginning of the end for the two of them. Ron thought it was a good idea to get us together for dinner to talk things over and smooth over the rough spots that had developed between the two men. But the gesture had been lost on Kip. Twice he had already complained about the food. He also brought up club issues which he felt were not properly handled. And now he was complaining about the wine. "You should have cooked the chicken longer," said Kip. "It's a little juicy." Even through the dim candlelight across the table, I thought I could see Ron's face slowly turn red. "I think it's fine," said Ron, coolly. Kip rolled his eyes and sipped his wine. "If you say so. Chicken was never meant to be cooked this way. You should read the directions more carefully next time." "Are we going as a group to Stellafane this year?" I asked, in an attempt to break up the tension. "I'm putting together a caravan," said Ron. "We'll meet in Manchester, hit the grocery stores, and go over as a group. Most of us HAMs - we can talk to each other on the way over." He seemed to perk up at the thought of this. "So Stellafane is now a social event?" asked Kip. "What do you mean?" I asked. Kip shrugged his shoulders. "Nothing, nothing. I'm just wondering, since when did Stellafane become a social event, that's all." There was an uneasy pause. "No one ever goes observing anymore," said Kip. This was clearly a slap at Ron, who is the most dedicated observer I have ever seen. He may miss club meetings and events, but he shows up at nearly every club observing session, every school skywatch, every community charity event. I have seen him leave one skywatch when it ended, only to pack up and go to another if it was still clear. He didn't seem to care, as long as he and one of his telescopes were under the stars together. Ron had the most extensive collection of telescopes I had ever seen. Years ago, he had started a chain of hardware stores in the area, and then sold them to one of the big warehouse chains when they moved in. Now retired at 37, he had a garage full of the most expensive, rare, and beautiful equipment imaginable. Once he had built an elaborate alarm system using some of the telescopes in his house, but he wound up dismantling it when it malfunctioned on him. "And besides," said Kip, doing a slow burn across the table, "no one ever contacted me about this caravan of yours." This seemed to confirm what he had suspected for years - when you needed something done, you called Kip. But if you wanted to relax and have fun, you avoided him. And if there was one thing that upset Kip more than not being able to run things his way, it was not being told when things were happening behind his back. "Tell you what," I said. "I'll go observing with you at Stellafane." I was ready to say anything, just to ease the tension between the two men. "No need," sighed Kip, waving me away. "I am twice the observer you are. You could never keep up." "Hey, don't talk to Ed that way," said Ron. "And besides, it's not true." "Suit yourself," said Kip, draining his glass. "But I am twice the observer any of you are. I can identify any object, any telescope. Just ask me." Ron stood up. He was a patient man but all the months of dealing with Kip were starting to take their toll on him. "You can identify any telescope, just by looking through it?" "Easy," said Kip. "Pick one of yours. Put a shroud over it with the eyepiece sticking out. I will identify it." "Pete, do you know how many telescopes I have?" "Thirty eight," replied Kip, without a moment's hesitation. "How did you know that?" said Ron. "I just bought a few more last month." "It makes no difference," said Kip. "And I will wager you on it." Ron sat down. "What did you have in mind?" Kip filled his glass slowly and drained it again. "Pick any of your telescopes. Throw a shroud or blanket over it. Allow me only to see the eyepiece. Show me any object in the sky. You do not even have to identify the object. I will know it soon enough anyway. I will return to this room and reveal the identity the telescope. "If I win, you resign as President of the club. You will not run again, not ever. The club bylaws state that in the event of a resignation, a runoff shall be held at the next meeting. You will support me. I know I am not a popular member, but with you supporting and campaigning for me, I will surely win. Then I will put back together this club of mine that you have destroyed. Ron ignored the swipe. "And if you lose?" "If I lose, I will resign from the club, permanently. You will never see me again." Ron and I gasped. Although the thought was appealing at first, it was hard to imagine. Kip had grown the club from an informal, local gathering of a few amateurs to one of the premier outfits in this part of the country in only a few short years. Despite his personality issues, he had undoubtedly been its greatest leader, and the man who put the club on the map. Such a thought -- an astronomy club without Pete Kip! "This is what you want, isn't it?" said Kip. "To get rid of me? Here is your chance." Ron sat, deep in thought. Then he spoke. "You and I have the same 20/20 vision. I will focus the image for you. You will not refocus." This was a reference to a parlor trick that Ron had once shown me. By defocusing the image, you could identify a Newtonian or a Catadioptric from a Refractor, and if you were good were good enough, you could make an estimate of its central obstruction percentage. Even without seeing the rest of the scope, you could make a fair guess as to its identity. Not being able to defocus the image would hurt Kip's chances, but not by much. Ron had all kinds of stuff in his garage --Classical Cassegrains, Ritchey-Chretiens, Schiefspieglers, etc. It seemed to me that Kip had set an impossible task for himself. "I will not touch the telescope or eyepiece at all," said Kip. Ron folded his hands on the table. "We have a deal." "I am only doing this for you," said Kip, returning from the restroom. We were alone together in the dining room. Ron had left the room twenty minutes ago and was busy setting up the mystery telescope in his driveway. "How so?" I asked. "Ron has ruined my astronomy club. I will not stand for it. Someone has to fix this mess. The bylaws state that the winner of a runoff election will only hold office through the end of the year. It is already September. Thus, I have three months to repair this club before -" "Before what?" I asked. "Before you become its next President," said Kip. "You see, I am only doing this for you." I was flattered by the sentiment, but not for long. Kip never did anything without careful planning. He was like a cat. He never jumped unless he was sure he could make it. His support of me only meant one thing - he felt he could control me, and run the club through me. Suddenly the prospect of becoming President became less than appealing. Ron appeared in the doorway. "I'm ready." "Then let's go outside," said Kip. We wandered outside, into Ron's driveway. It was clear, dark, and quite cold for September. Ron lived at the top of a hill overlooking the town. He picked the location specifically for astronomy purposes, away from city lights. Despite his careful planning, though, a little dome of light had grown towards the east, partially obscuring one of his horizons. The scope sat in the middle of the driveway. Or, what we could see of it anyway. There was a large black curtain directly in our path, twelve feet high and at least twenty feet across. In the middle of the curtain, about half way up, was a small ½" X ½" cutout with a tiny little eyepiece sticking out at an angle. Ron had been very thorough. The scope could have been a small Newtonian on a raised platform, a refractor with its diagonal purposely twisted at a strange angle, a Schmidt-Cassegrain on an extended tripod, or a really big Dobsonian pointing towards the horizon. It was impossible to tell. I approached the eyepiece. It was dark enough near the curtain that I couldn't even tell for sure what kind of eyepiece it was. I would have guessed it was a Plossl or an Orthoscopic of medium focal length, but I wouldn't swear to it. Ron had done an excellent job of concealing the scope's identity. "Come on out, Pete," said Ron. Kip emerged. He approached the curtain with sure and steady steps. It was dark enough that Ron had to guide him to the eyepiece. Kip leaned in to look through the eyepiece, then pulled back. "I want to make absolutely certain that you want me to do this," he said. "Once I look through this eyepiece, this bet is officially on. There can be no backing out." There was a short pause. "We have an understanding," said Ron, in the darkness. Kip leaned in again, and looked through the eyepiece. What happened next was uneventful. He stood completely still. He did not touch the eyepiece, and did not try to look behind the curtain. Truth be told, he didn't even seem all that interested. After perhaps a minute or so, he pulled back. I expected him to take a lot longer. After all, we were talking about Kip's future with the club, something I knew he cared deeply about. Kip stepped away and wandered casually back towards the house. While he did this, I snuck a peek into the eyepiece. There was a star in there. Nothing more. I had no idea where the telescope was pointed, and no idea of the aperture of the instrument, so it was impossible to tell what star it was. It looked perfectly ordinary to me, the way Capella or Procyon might look in a run of the mill 8" Schmidt Cassegrain. "I'm ready," said Kip. Ron had cleared the table and had set out dessert - cookies and ice cream. Kip dug in with gusto and asked for seconds. "You should serve the cookies separately," he said. "They get soggy when they sit next to the ice cream for too long." After we finished, Ron was impatient. "All right, all right, spill the beans. What do you think?" Kip wiped his mouth and set the handkerchief on the table. Then he leaned back in his chair, and appeared lost in thought for a moment. When he finally did speak, it was quietly, in that calm, analytical voice that all of us knew so well. "Well. You gave me the image of a star, or a stellar-like object. It was probably too much to expect that you might give me something easily identifiable, like the Ring, or the Dumbbell. If you did that, I might have had a fighting chance. I might have been able to tell magnification, approximate aperture, etc. and make a guess from there. But you did not do that. You gave me a simple stellar image. Something I have no hope of working with. Do you really dislike me that much, Ron?" "We had a bet," said Ron. "Yes," replied Kip, "but one in which I apparently have no hope of winning." A long pause. "So that's it, then," said Ron. "Apparently so," said Kip. Ron rose, and picked up the dishes from dessert. He was trying to contain himself, but there was an obvious spring to his step. Just as he was about to disappear into the kitchen, Kip spoke again. "But then again..." Ron stopped dead in his tracks. "I do have one guess, don't I?" No reply from Ron. "There was a stellar image in the telescope," continued Kip. "You picked a fairly dim star, but one not dim enough, I'm afraid. It was bright enough that I could see the absence of any diffraction spikes in the image. So we may rule out any conventional Newtonian with a two, three, or four-vane secondary. Now, this could have been a Newtonian with a curved secondary, but my guess is that you are not a curved-secondary kind of guy, am I right, Ron?" He did not wait for a response. Kip continued. "So we are left with a Refractor or a Catadrioptric-type of telescope. Knowing your love of Newtonians, this removes close to half your telescopes from consideration. Also, while I do not know the exact aperture of the telescope in question, my guess is that you did not bring out one of your larger instruments. A good ploy, using that huge black curtain, but my guess is that the telescope is a relatively portable one. "I have been to your house many times for observing, Ron. If you had bothered to come over to talk to me once in a while you would know how much time I spend under your dark skies here. You have very little sky glow around these parts, but you do have some. In a larger telescope, say twelve inches and up, there is a noticeable brightening of the sky background. I saw none in the image. So my guess is that the telescope is of eight inches of aperture or less, possibly a lot less. Also, I saw no wavering of the image, which suggests the telescope was used at relatively low power. This eliminates all of your larger Mak-Newts and all the conventional C8s and LX10s you have lying around here. "So we are left with a small refractor or smaller Schmidt Cassegrain. I know you are not a fan of the latter so we can concentrate on the refractors. I saw no purple halos, no false color of any kind, and the star was a pure white color, so we may rule out the achromats. The image looked a little too bright for any three inch telescope so my guess is that it's a four inch, or thereabouts. In this class of smaller apochromats I know you are a fan of the Takahashi units, specifically the FS102, which I have seen many times. It is, in fact, your favorite telescope. "You tried to hide in plain sight, Ron. It did not work. This telescope was your Takahashi FS102. Ed, would you care to step outside and verify my guess?" Ron stood stone still, but motioned for me to sit when I got up. A long pause. "I demand to know how this was possible." Kip sighed. "Simple deductive reasoning. As I said, I am twice the observer any of you are. You should have been more careful." "This is not possible." Kip rose. "Oh yes it is, Ron. And as the club Treasurer, I now officially ask for your resignation from the club." Ron set the dishes on the table. He looked like a defeated man. Through these nine months of battling with Kip, it was hard to believe that it was ending this way. "I gave you my word," said Ron. "You have my resignation." "Shall I make the announcement, or do you want to do it?" "I will do it, thank you," said Ron, barely able to contain himself. "Do it soon, Ron. I want to make my intentions towards the Presidency known right away," said Kip. "And with that, I will take my leave. Thank you for dinner. You should invite more guests next time." "I think I'd better leave too," I said. Later, in the driveway, I met up with Kip, who was ready to get into his car. There was a calmness about him that was not there at the beginning of the evening. I wondered how the club was going to react when they heard he was going to be President for the next three months. Some officers would probably resign. Others would tough it out, hoping for the best when election time came around again. In a way I felt sad for him; he was not comfortable in any situation unless he had absolute control. I think that being President of the astronomy club was the only thing that really ever made him happy in life. Almost before I knew it, I blurted out what was on my mind. "Tell me how you did it," I said. Kip flinched. It was the first time I ever saw him do so. "What do you mean?" "You know what I mean." Kip paused, as if to gauge me. "Ron's resignation is permanent. I will not have it revoked." "I'm not asking for that. I just want to know what happened. What really happened." Kip paused. "You will tell no one." "I will tell no one." Kip looked at me, as if studying me. Then he spoke. "While Ron was in the driveway setting up the scope, I went upstairs into the bathroom overlooking the front of the house. I saw him drag out the Takahashi and hide it behind the curtain. When I was in the garage later, all I had to do was check that the Tak was missing. It was. It had to be the one." Now it all came together. His nonchalance at the eyepiece, his confidence. The outcome was never in doubt. Like a cat. He did not jump until he was sure he could make it. "You cheated." "It was never stipulated that I could not cheat. All I said was that I would not touch the telescope or the eyepiece. I did not. I played by the rules set forth between us. As I told you earlier," he said, getting into his car, "I am doing this for you. I only have the best interests of the club at heart. I look forward to working with you next year, Mr. Future President." Kip started up his car, put it in gear, and drove away. Behind me, the Takahashi stood in the driveway, waiting for an observer to take the controls. I glanced up at the inky black sky, and then down to the base of the driveway. Kip's taillights flashed as he hit the brakes, then dimmed, looking like a pair of distant red flashlights underneath the cool blanket of the clear sky above. -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

Tales of Astronomy Ι, Ed Ting, 1999 "Ed, you gotta help me!" I stumbled, bleary-eyed, to the front door and looked the clock on the wall. 2:32 AM. "Ed, come on -- open up, please help!" Someone was pounding on the front door. Shaking off the cobwebs in my mind, I flipped on the porch light and peered outside. Behind me, Ewok the cat hid behind my legs, pacing curiously back and forth. I opened the door. "Oh, thank God!" He burst inside. It was Ron, a neighbor from a few blocks away and a member of our local astronomy club. He was un- shaven, his hair was standing straight up, and he was wearing a white bathrobe and slippers, both of which were grass-stained. "Ron, what's wrong?" I asked. "Ed, you gotta help me. You have to help me break back into my house." "OK, Ron, calm down." I could see he was in a near panic. "What's this, you have to break into your house?" "Yeah," he said, "I stepped outside on the back deck after arming the security system to the house and a gust of wind slammed the door shut behind me. My wife left earlier this evening to be with some friends, and she's due back any moment. If she trips the alarm and the police come over again, she's gonna kill me." He stopped for a moment and caught his breath. " I ran all the way over here, and I'm desperate." People sometimes thought he was a little eccentric, but I always liked Ron. At one time or another, he'd owned just about every model of telescope ever made. I don't think I'd ever seen him show up with the same scope at a star party twice. When he got tired of the scopes, or needed more space, he'd donate the old in- struments to local schools or churches. I remembered the first time I visited him. The house was piled high with model trains, ham radio equipment, audio equipment, photographic equipment, and, of course, telescopes. Lots of telescopes. I couldn't find a place to sit down because all of the chairs in the house had optical tubes draped across them. "What do you mean again, Ron. Has this happened before?" "Well..." he looked down at his feet, as if embarrassed. "I've been playing with the system for the past few months -- you know, enhancing it." He looked up at me. "The trouble is, during the test phase I kept tripping the alarm, and police kept showing up. It's a long way out to the house, and they're tired of wasting their time. Now they've told me that if they get another false alarm, they're going to consider arresting me. You have to help me break into my house and disable the alarm before Shelley gets home." "OK, I'll help," I said. Taking mental inventory, I began to wonder what I'd bring. Night-vision binoculars, perhaps? A crowbar? A flashlight? "Thanks, I really appreciate it," said Ron. "Here's what we'll need. Can you get me a large cardboard box, a stopwatch, two ski masks, and a can of cat food?" He looked down at Ewok, now sleeping peacefully in a corner. "Can your cat travel?" "Uh...No," I said. "He's an indoor cat." I started to gather the things Ron had listed. I didn't bother asking why, but I did begin to wonder: exactly what kind of alarm system were we dealing with, anyway? "This is the world's first telescope-based home security system," said Ron, later. "I am going to patent it." We were in my truck, driving back to his house. I looked over at him. I had given him some of my old clothes, which didn't quite fit. My shirt was a little tight on him, and the jeans I'd given him rode up, revealing his legs. He looked like a character from a bad sitcom. To his credit, none of this seemed to bother him. In fact, I sensed an element of pride in his voice. "A few months ago, while installing a new alarm system in the house, I decided to put some of my old scopes to use." He checked his watch. "Shoot -- it's almost 3 AM already. Can you drive faster? "The telescopes are integrated into the security system and acts as its eyes. I modified the equatorial mounts on the scopes to slew back and forth across my property to search for intruders. In a way, they're like 'Goto' mounts except that they always 'Goto' the same places, over and over again. The telescopes operate in pairs, with each pair sweeping out a defined area of the yard. "The first telescope in each pair is an Orion Short Tube, a low power, wide- field scope. There's a CCD camera with a night-vision enhancing chip mounted at prime focus. As the scope slews across the yard, the CCD takes images at a number of predetermined positions on the property. The computer then compares the images with the ones stored in memory and notes any discrepancies. If it finds something suspicious, it automatically slews the second telescope -- a CCD-equipped Meade 7" refractor operating at a higher power and heavily modified for super-fast slewing -- to the same location and takes a close-up image of the suspected intruder. "Then what?" I asked. Ron sighed. "If the system discovers an intruder, it automatically turns on all of the lights in the house. Then, the 16" Dobsonian slews on its equatorial table and spotlights his location. I modified a high-intensity-discharge halogen lamp and attached it to the Dob's focuser. Once the light is energized, the big Dob acts like a giant searchlight. Then the outdoor PA system announces to the intruder that he is surrounded and that it's in his best interests to stay put. A computer-generated phone call is placed through the modem to the police, informing them of the time, location of the residence, and the position of the intruder. The same computer generates an e-mail with the same information and attaches a jpeg of the image taken by the scopes. "At this point all of the telescopes are aware of the location of the intruder. If he tries to run away, the scopes will simply track his direction of departure and continue feeding e-mails and jpegs to the police as long as they can." "Uh huh," I said, trying to comprehend. "Ron, can't you use simple door and window alarm switches, or motion sensors, like everyone else?" "Actually, I do. There different levels of sensitivity to the system -- you just dial in the level that suits you. At its most basic setting, only the door and window sensors are armed. As you turn up the sensitivity, first the Short Tubes, and then the big refractors come into play. "The problem is, just before I got locked out, I'd set the system to 'infinite' mode. It's just a test setting that I devised -- I never intended for anyone to actually use it. Everything is hypersensitive, on a hair-trigger response, at this setting. "So...tell me, how exactly are we going to past all of this?" Ron didn't respond for a while. Instead, he motioned for me pull off the road into a driveway. "Well...I have a plan. It just might work. But we don't have much time. Here, kill the ignition." I did, and the truck sputtered to a stop. "The Peterson's have a cat named Chester. He's usually out at night and visits me when I'm in the dome in my house. He's an outdoor cat, not like Ewok. Get the box and the cat food." I looked out of the side of the truck. We were at the head of a long driveway. A single floor ranch lay at the end of it. There were no lights on in the house. At the head of the driveway stood a mailbox. In the moonlight, I could read: "Peterson." "OK," said Ron, "open up the can of food." I did so and waited. I looked up. The night was still, and the stars were barely twinkling. I briefly thought to myself that this might have been a good night to go double star observing. Not long afterwards, I saw something small and gray darting in and out of the shadows. "Here, kitty-kitty-kitty," said Ron. "Get ready with the box, Ed." "Are we kidnapping this cat?" I asked. "Are you sure this is right?" "It's only for a while," he replied. "Besides, we'll return him when we're done." Chester approached us, tail wagging cautiously behind him. I held out the can and he sniffed at it. "Scoop out some food and put it in the box," said Ron. I did, and Chester purred happily and hopped inside. "OK," he said, closing up the box, "Let's go!" A few minutes later we pulled off the side of the road again. "I don't want to get too close to the house. We walk from here." We got out of the truck. I lifted the box and felt a weight shift inside. Chester meowed in protest. "Here, stay low," said Ron, crouching behind some bushes. "OK, now, let's move up to the hedges." I got down on all fours, pushing the box ahead of me. The dew on the grass soaked through my knees. Once up to the hedges, Ron motioned for me to come up alongside him. "Careful," he said, "Have a look. And whatever you do, don't stand up or make any sudden moves!" Carefully peeling away the top layer of the hedges, I held my breath and looked up at the lonely house in the distance. Ron's house sat at the top of a small hill, about a hundred yards away. I could see why he had chosen this location for his house. It was the highest point in the area, and his observing horizons were excellent. There were no trees. The property looked like a bald, grassy hill with a house at the top of it. The house itself was a long and low custom ranch, which curved inwards like a crescent moon. At one end of the roof sat a shiny dome. Ron signaled me to follow, and we edged along the hedges to the front gate. There was a metal sign on it: "Trespassers, Take Note! You ARE BEING MONITORED AT THIS VERY MOMENT. DO NOT ENTER Without Permission! Police WILL Take Notice!!" "Ron, if this security system is so sophisticated, how did you get away from it?" "I almost didn't. You see, each pair of scopes is responsible for one of four zones -- the front, the back, or the two sides of the house. I laid out the zones so there aren't any seams between them, but it does take time - twenty seconds on the side zones and close to thirty on the front and back - for the Orion Short Tubes to slew across those zones. I knew this, and once I caught a glint of light through the rear bay window, I knew the scope was beginning its scan. I ran as fast as I could, and managed to get away. "It occurred to me while running over to your place that we can simply do the same thing in reverse. It's possible to sneak in behind a particular area of the yard just after it's been scanned. Hopefully, we can be inside the house before the scope returns to the area. "I have a key to the back door hidden under the back deck. At the time, I didn't even think about it. I was so worried about setting off the alarm, I just ran away as fast as I could. "We'll need more than thirty seconds to run across the back lawn, get the key, and open the door. The system is programmed to recognize small animals like dogs and cats. We'll get Chester to run across the lawn. He'll distract the scopes. It takes a moment for the system to process the fact that Chester is a cat and not an intruder, and that will buy us some time." "So...how much time are we talking about?" I asked. "In total?" Ron thought for a moment. "Maybe forty seconds or so." We began to work our way towards the back of the house, taking care to stay low and just below the line of sight of the scopes. "Ron, you've tested this animal- recognition system, right? I mean, it will know Chester's a cat and not set off the alarm?" Ron looked away. "Er...Look, I haven't got time for all your questions. Just follow me, Okay?" A few minutes later, we were looking at the back of the house, and the back yard. We worked our way slowly up the hill, until Ron signaled for us to stop. "We can't get any closer," he said. He pointed towards the bay window in the back of the house. "Watch the window. Every once in a while, you'll see a little flash of light. That's the reflection off of the Short Tube's lens. After one of those flashes, we make a break for it." I peered off into the window, perhaps a hundred yards or so away. Sure enough, within a few seconds, I saw the tiny flash. A short time later, I saw it again. The time in between didn't seem like nearly enough. "Where's the 7-inch Meade?" I asked. "I don't see it." "Right behind the Short Tube," said Ron. "Nominally, it's horizontal, and aimed out towards the yard. It's probably pointing straight at you right now." Ron put on his ski mask and advised me to do the same. Then he took out the stopwatch and reset the pointer. "All right -- here's the plan. We open the box, and let Chester sniff the cat food. Then you throw the can to one end of the zone. In this case, it's that corner of the yard," he pointed, "away from the door we'll be using to get into the house. The scopes will take over, we make a break for it, I get the key, unlock the door, and we duck inside before the scope can slew around again. Got it?" "Got it," I said. If this somehow failed, I wondered how I'd explain to the police why I had abducted a cat and was now wandering around someone else's back yard wearing a ski mask. "One other thing. It's important that you follow my footsteps exactly. Don't set foot anywhere I don't step. There are multiple motion sensors hooked up around the yard, and I know all of the dead spots. So you have to follow me exactly. Understood?" "Yeah," I said, wondering how I had allowed myself to get involved in this. "Are you ready?" asked Ron. I nodded. I opened the box. Chester meowed in greeting as I picked him up. Ron took the can of cat food out of his pocket and held it under the cat's nose. Chester began squirming and purring. Ducking low, Ron took the can and hurled it towards the corner of the yard. Chester broke free of my grasp and bounded after it. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the little flash in the window as the Short Tube slewed past. A split-second later, I saw a much larger flash somewhat higher in the window. Presumably, it was the 7" locking on target. Ron clicked the stopwatch. "Go!!" We jumped up and into the yard. Ron hopped forward like a frog, then side- stepped to the left. Then he sprang forward into a forward roll. Then he side-stepped again. I followed dutifully. We must have looked like two drunken potato-sack racers. It seemed as though we were moving in slow motion, as if in a dream, doing some sort of cosmic Jitterbug. After what seemed like an eternity, we both reached the deck, breathing hard. "The key's under here," said Ron. Too scared to move, I looked into the bay window. The Short Tube was pointed away from us. It was slewing back and forth in tiny, jerky increments as it tried to follow Chester's movements. Above it, like a big brother, the 7" refractor loomed, pointing in the same direction. Suddenly, the big scope reversed direction and came back to its rest position. Not long afterwards, the Short Tube had resumed tracking normally as well. "The scope gave up on Chester. It's coming back!" I said. Ron pulled his hand from under the deck. "Got the key!" he said. We scrambled onto the deck and almost collided together into the back door. The Short Tube had reached the end of its travel and was now slewing back towards us. Ron fumbled nervously with the key fob and somehow, despite his shaking hands, managed to insert the key correctly and turn the doorknob. We burst into the house and slammed the door behind us. I fell on the floor, panting. In the next room, I could hear the humming of the scope's motors as they resumed tracking. Ron flipped on the light switch and held up his hands. "That was close. Don't worry, we're safe now. The system is designed to protect people inside the house." He motioned towards the kitchen table. "Here, sit down," he said, and then corrected himself. "Oh yeah -- you can't sit down. There are scopes in the chairs. Sorry." "That's OK," I said. "I'm too wound-up to sit down anyway. I'll just stand. Say, are all your evenings this exciting?" Ron seemed to be in a far-away place when he answered, "Nope..." "What's wrong?" He sighed. "I just invented the most advanced home security-system known to man, and now I've defeated it twice in the same evening." "What are you saying, Ron? You should be thankful we got into the house!" I looked around at all of the optical equipment lying about, and shook my head. I couldn't believe the way this guy lived. Scopes and parts lay scattered about everywhere. Somehow, I knew that, by tomorrow morning, he would be tinkering with his parts again, making the system even better. "If I can figure out a way to manufacture darker multi-coatings, perhaps I can eliminate those tell-tale flashes off the lenses in the window," mused Ron, as if reading my mind. I heard a scratching at the front door. I tiptoed around the scopes and parts lying on the floor and looked out. It was Chester, on his hind legs. He flipped his tail when he saw me through the glass. "Hey, Ron -- we still have to get Chester back home," I shouted. "Gotcha," came the reply from the other room. "In just a minute. I'm going into the hallway to disable the alarm." "OK, I'll get him!" I said. "Chester," I teased, tapping at him through the window, "Good kitty." I opened the front door to let him in. "WOOOoooWWWooooWWWoooOOOO!!!" The lights in the house suddenly all came on at once. A siren began braying outside. "THIS IS YOUR FIRST AND LAST WARNING," blared a voice, which sounded suspiciously like Darth Vader's. It was so loud that I barely think. "DO NOT MOVE. YOU ARE BEING MONITORED!" "WWHHOOoooooOOOOOoOOOOOoooooWWWooooo!!" The telescopes next to me began slewing towards my location. In the light the scopes looked like some sort of erector-set monstrosities concocted by a mad scientist. Colored wires hung off the mounts, and hand-wired circuit boards were duct-taped to the optical tubes. The 16" Dob locked on to my position and almost blinded me when its high-intensity discharge lights switched on. Ron came bounding in from the other room. "What did you just do?!" "WWHHoooHHHWOoOOOOooooo!!" I had to shout to be heard above the blaring sirens. "I let the cat in!" "No! The door alarms are the most basic level of protection of all!" He said. "They're always armed at night! Always! Oh no!!!" All around me, computers came to life. Once-dormant monitors blinked on with little splashes of static. I heard dial tones and modem signals. Printers began whirring. Chester, frightened by the noise, jumped up into my arms and began clawing at my shirt. "WWWOOOoooOOWWWWOoooooooWWhhhOOOOO!!!" "Ron, is that..." "Yes!" he screamed, over the din. "It's James Earl Jones' voice! I recorded all of Jones' movie and TV appearances, as well as his CNN promos. Then I had the computer synthesize a digital bit stream of his voice!" "Oh NOOOOO!!!!!" The last thing I recall, after looking down the barrels of the scopes, was a CCD image of myself on one of the monitors, with a panicked, exasperated look on my face, and trying to peel a cat off my chest... "WHHOooooOOOoooOOO..." "OH N-" "Ed, you gotta help me!" I sat bolt upright in bed, drenched in sweat, and looked around. There were no sirens, no computers, no telescopes slewing on their mounts. I was safely back home. All was quiet, except for the telephone receiver squawking away in my lap. A dream, I thought. A bad dream. "Ed, are you still there?" I picked up the phone. It was Ron. "Yeah, Ron...I'm here. I...uh...I guess I fell asleep." I had a cat digging its claws into my shirt. It was Ewok. He probably saw that I was having a dream and was now clinging to me out of fear. "How could you fall asleep? We were talking about what I should do with all of my spare telescopes, remember? Should I sell them, or donate them to the club?" "Ron, I...uh...well, I don't know. Can we talk tomorrow?" "Sure. I have to go anyway. I see my wife coming up the driveway." "Be sure and disable the alarm," I mused. "What? I don't have an alarm system. Say, think I need one?" he asked. "Uh -- No. No, you don't!" "OK -- Hey, good idea, though....Alarm system, eh? Hmmm..." said Ron, and hung up. I got up, knowing that sleep would not be possible for a while. In my living room a few minutes later, I watched the stars twinkling through the bay window with a warm cup of milk in hand. Ewok lay curled up and purring at my feet. I looked up at the clock. 2:32 AM. Looking out of the window, I couldn't help but expect a lonely, half-crazed figure to come running down the street towards my house. It was, of course, too crazy to happen. It couldn't happen. It just couldn't. Could it? -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

Rockets Through Space: The Story of Man's Preparations to Explore the Universe, Lester Del Rey, James Heugh, 1957 -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

Rockets Through Space: The Story of Man's Preparations to Explore the Universe, Lester Del Rey, James Heugh, 1957