-

Αναρτήσεις

16264 -

Εντάχθηκε

-

Τελευταία επίσκεψη

-

Ημέρες που κέρδισε

26

Τύπος περιεχομένου

Forum

Λήψεις

Ιστολόγια

Αστροημερολόγιο

Άρθρα

Αστροφωτογραφίες

Store

Αγγελίες

Όλα αναρτήθηκαν από kkokkolis

-

Δεν πειράζει Τάκη, θα αγοράσω από την Agena. Του έβαλα καπάκι από τον παλαιότερο Barlow και σε εκείνον έβαλα δοσομετρικό ποτηράκι από σιρόπι Ceclor, ταιριάζει μια χαρά. Επι τη ευκαιρία είναι φοβερός Barlow, όπως τον ήθελα, κοντός με μεγάλο group φακών και φωτεινός. Αν και ο Celestron είναι έτσι τους προτείνω.

-

Concenter Mark II - ευθυγράμμιση δευτερεύοντος

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της vlahmapoutras σε Τηλεσκόπια

Για να στοιχηματίζεις εμβριθώς και ενήμερος, 18:00-22:00 (κατά περίπτωση 24:00) ώρα πατρίδας ΔΕ-ΠΕ: μεροκάματο. Μουλάρι ο Αστραχάν! Τις υπόλοιπες ώρες ενεδρεύω. Πόνταρε όλα τα λεφτά. -

Ευχαριστώ πολύ. Είχα ξεχάσει αυτά της Agena, νομίζω πως η ποικιλία της με καλύπτει.

-

Χαίρετε. Θα ήθελα να μάθω αν έχει αγοράσει κανείς προϊόντα από το http://www.eyepiececaps.net/servlet/StoreFront Νομίζω πως έχω δει σε κάποια αγγελία προσοφθαλμίων του Astrovox τα χαρακτηριστικά αυτά κίτρινα καπάκια. Στέλνουν και στην Ευρώπη; Υπάρχουν εναλλακτικές πηγές από Ελλάδα ή Ευρώπη; Αν τα έχετε δοκιμάσει, έχουν καλή εφαρμογή; Το προσοφθάλμιο στέκεται όρθιο σε ένα τραπέζι με βάση το καπάκι του αντικειμενικού; Το κόστος είναι ασήμαντο, αλλά εάν υπάρχουν καλύτερες εναλλακτικές θα ήθελα να το γνωρίζω. Υπάρχει παρεμπιπτόντως κάποια πηγή για καπάκια τηλεσκοπίων (150 & 80mm); Έχω δει καπάκια τύπου σκούφου, αλλά προορίζονται για μεγαλύτερα τηλεσκόπια συνήθως. Ευχαριστώ για τον χρόνο και τον κόπο σας.

-

Έφτασε. Ο φακός φαίνεται μια χαρά αλλά δεν είχε καπάκια; Ή μήπως ξέχασες να τα βάλεις; Γνωρίζει κανείς που μπορώ να βρώ καπάκια; Έχω ένα ζευγάρι από ένα Plossl που μετέτρεψα σε σκοπευτικό ευθυγράμμισης, αλλά το άνω είναι για φακό 1.25 και όχι για Barlow. Αν πρόκειται για κάποιο κατάστημα του εξωτερικού θα παραγγείλω μεν αλλά μαζί με κάτι μεγαλύτερο. Μέχρι τότε;

-

Για να μην τα συγχέουμε, οι φορητές εφαρμογές που ανέφερα είναι για Windows (υπάρχουν και για Linux). Πρόκειται για εκδόσεις δημοφιλών προγραμμάτων (υπάρχει και το Mobile Office!) οι οποίες έχουν τροποποιηθεί από προγραμματιστές ώστε να μην χρειάζονται εγκατάσταση ή να πραγματοποιούν μια ταχύτατη εγκατάσταση και αυτόματη απεγκατάσταση από τον υπολογιστή μετά την έξοδο από το πρόγραμμα. Έτσι τις φορτώνεις σε ένα flash memory ή έναν φορητό σκληρό δίσκο (έχω 4 GB τέτοιων εφαρμογών σε τρία αντίτυπα, στον Western Digital Passport, μία κάρτα SD και ένα USB flash) και τις μεταφέρεις μαζί σου, ώστε να δουλεύεις τις δικές σου εφαρμογές σε οποιονδήποτε υπολογιστή (σπίτι, δουλειά, εξοχικό, ξενοδοχείο, internet cafe, φορητό, το PC ενός φίλου κλπ). Οι υπόλοιπες εφαρμογές που περιγράφετε προορίζονται για κινητά και Palmtop. Εφ' όσον το αναφέρετε πάντως, για όποιον δεν χρησιμοποιεί Palm, PPC, iPod ή iPhone, κινητό Symbian κλπ, οι εφαρμογές Mobile Star Chart & Sideralis είναι πολύ καλές για υπενθύμιση του τι υπάρχει ψηλά. Υπάρχουν ώρες που το μόνο που κουβαλάμε πάνω μας είναι το κινητό και μέχρι να καταφέρει να στριμώξει κάποιος Νομπελίστας προγραμματιστής την Uranometria ή το Starry Night πλήρως λειτουργικά σε ένα Java κινητό αυτές οι εφαρμογές μπορούν να διασκεδάσουν εκπαιδεύοντας ή και το ακριβώς αντίθετο.

-

Θα με βοηθήσει το DIOPTRX;

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της Τάσος Βράτολης σε Προσοφθάλμιοι φακοί

Ενδιαφέρον: 1. Η εικόνα μεταβιβάζεται στο δεξί ημισφαίριο, προκαλώντας συναισθηματικούς συνειρμούς. Άρα η αντίληψη θα είναι ευκολότερη. 2. Δεν μου κάνει εντύπωση. Είσαι μουσικός και αισθηματίας. Εμένα δυστυχώς πάει στο αριστερό, στο ημισφαίριο του λόγου (ξέρω, δεν σου κάνει εντύπωση). 3. Με το αριστερό θα πρέπει να βλέπει ο οφθαλμός προς την μύτη. Έτσι θα πηγαίνει στο ίδιο ημισφαίριο. 4. Αν το αστιγματικό πεδίο είναι προσωτιαίο δεν θα έχεις σημαντικό πρόβλημα! 5. Αν είναι παραρρινικό ίσως με μια καλή εστίαση να διορθώνεται 6. Αν είναι προς το μέτωπο ή το ζυγωματικό ή περιμετρικό το πρόβλημα θα υφίσταται. Αλλά στα DSO's η εστίαση είναι ούτως ή άλλως ασαφής, οπότε η διαφορά μικρή. 7. Συμπέρασμα: αν αφήσεις κατά μέρος αστρικά πεδία και πλανήτες και εντρυφήσεις σε αχνές ασάφειες με πλάγια διόπτευση στο δεξί οπτικό πεδίο του αριστερού οφθαλμού θα είσαι αρκετά λειτουργικός Αυτό είναι υπόθεση. Δοκίμασέ το. -

Θα με βοηθήσει το DIOPTRX;

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της Τάσος Βράτολης σε Προσοφθάλμιοι φακοί

Μια άλλη λύση, όχι φθηνότερη από την Dioptrix αλλά με την δική της γοητεία, είναι ένα διοφθάλμιο. Και εκεί το ένα μάτι θα συμπληρώνει τα κενά του άλλου και με το δικό σου τηλεσκόπιο υπάρχει σχετική περίσσεια φωτός. Βέβαια θα χρειάζεσαι διπλά προσοφθάλμια. Όταν παρατηρείς με πλάγια διόπτευση (με το επικρατές μάτι), προς τα που έχεις την τάση να κλίνεις την κεφαλή ή να στρέφεις τον βολβό; Η κόρη πάει προς την μύτη ή προς το αυτί; -

Πλανητική παρατήρηση με Dob 8"

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της netrionio σε Παρατήρηση Πλανητών

Ποιό είναι το πρόβλημα της παρατήρησης πλανητών που αναφέρεις; Πρέπει να βλέπεις μια χαρά τους πλανήτες, εγώ τους βλέπω με 5 και 6 ίντσες και είμαι ευχαριστημένος. Ο Κρόνος και ο Άρης δεν είναι σε ευνοϊκή εποχή (ο Άρης ήταν πολύ καλός τον Χειμώνα, δεν το ήξερα τότε επειδή δεν τον είχα δει όπως είναι τώρα). Τον Δία τον έχεις δει; Θα ανατέλλει όλο και νωρίτερα, τον είδα προχθές με τα Skymaster στις 4:20 και σε σχέση με τον Κρόνο φαινόταν τεράστιος, είδα και 3 δορυφόρους με το κιάλι. Οι διαφορές που βλέπω εγώ μεταξύ ορθοσκοπικών BGO 9 & 6, Nagler 7, Υπερίων 8 και Υπερίων Zoom στα 8mm είναι μηδαμινές. Στο κέντρο είναι αρκετά κοντά το ένα με το άλλο, όλες οι διαφορές είναι στην περιφέρεια. Αυτό για τα δικά μου μάτια, τα οποία δεν συγκαταλέγονται ανάμεσα στα καλύτερα στον κόσμο, εξ' ού και η αγάπη για τα οπτικά βοηθήματα. Ακολουθώ την συμβουλή του Σοφολόγη να μην μεγεθύνω υπερβολικά (επιλέγω προσοφθάλμιο κοντά στον εστιακό λόγο του τηλεσκοπίου, πχ 9mm BGO για το f/10 SCT και 6mm BGO για το f/5 Νευτώνιο) και οι πλανήτες φαίνονται καθαροί, σαν να έκοψες το περίγραμμά τους με ένα νυστέρι στο βελούδο του ουρανού. Για τα DSO's φυσικά μεγάλο τηλεσκόπιο αλλά και σκοτεινός ουρανός, αλλά σε τι ισημερινή θα φορτώσεις ένα Νευτώνιο 20 κιλών χωρίς τα προσοφθάλμια και μήκους πάνω από 1.5m είναι ένα θέμα. Τι ταλαντώσεις θα κάνει; Πως θα αντιδρά στον άνεμο; Όταν λέμε πως το 12'' Dobson, ακόμη και Flextube είναι δύσκολα μεταφερόμενο, τι θα συμβαίνει με αυτό; Για το 8ρι πάντως αυτή η βάση φαίνεται μια χαρά και μπορείς να βάλεις και άλλα πράγματα επάνω. Νομίζω πολλοί έκαναν αυτήν την αναβάθμιση. -

Το Υπουργείο Παιδείας μπλοκάρει της Ολυμπιάδες Μαθηματικών

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της vossinakis σε Η αστρονομία στην Ελλάδα

Δεν υπάρχει περίπτωση να την διαβάζει. Μάλλον την συμπληρώνει ο image maker (face maker?) και οι γραμματείς της. -

To Plus όχι. Έχει GPS αλλά είναι απενεργοποιημένο μέσω λογισμικού, λόγω κακής λειτουργίας. Αλλά το GPS το είχε μόνο για συντεταγμένες. Την εύρεση στον ουρανό την κάνει με ηλεκτρονικό αλφάδι και πυξίδα προσανατολισμού, υπολογίζει δηλαδή την θέση της "κάννης" ώς προς το αζιμούθιο με την πυξίδα και ως προς το ύψος με τον αισθητήρα κλίσης (αξελερόμετρο; ) και μετατρέπει σε ορθή αναφορά και απόκλιση που σε συνδιασμό με το ρολόι και τον εσωτερικό χάρτη κάνει την εύρεση.... όταν δουλεύει.

-

Θα με βοηθήσει το DIOPTRX;

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της Τάσος Βράτολης σε Προσοφθάλμιοι φακοί

Τάσο, αν αντί για Panoptic είχες τον Hyperion 24, υπήρχε περίπτωση να αλληλοεξουδετέρωναν το ένα το άλλο ως προς την κόμη! Πλάκα κάνω (αλλά πλάκα- πλάκα υπάρχει και δόση αλήθειας). Για το Dioprtix δεν θα σου πω καθώς δεν το έχω, απαντώ κατ’ αρχάς για να σου πω περαστικά και επειδή χθες προσπάθησα να δω πολλά πράγματα με το αριστερό μου μάτι προσπαθώντας να διαφυλάξω το δεξί ψάχνοντας να δω τι φαίνεται από την θέση που είμαι προς την Παρθένο και τον Σκορπιό. Λοιπόν, ήταν αδύνατο να ΑΝΤΙΛΗΦΘΩ αυτό που έβλεπα όπως είχα συνηθίσει, εννοώντας πως δεν υπήρχε τόσο πρόβλημα προσαρμογής στο φως, όσο μεταφοράς του ερεθίσματος μέσω των οπτικών οδών προς τον ινιακό λοβό και από εκεί στα αντιληπτικά και συνειρμικά πεδία. Αυτό όμως το πρόβλημα, όπως όλα τα προβλήματα πλαγίωσης, μπορεί να λυθεί με την εξάσκηση που οδηγεί σε συναπτογέννεση, όπως ο κιθαρωδός μαθαίνει να δουλεύει και το αριστερό του χέρι στην ταστιέρα και ο πιανίστας να κάνει συγχορδίες με το αριστερό ή και μελωδία με το δεξί όταν είναι αριστερόχειρ. Αυτό όμως χρειάζεται χρόνο, τον οποίο ελπίζω να μην τον έχεις, καθώς εύχομαι να γίνεις σύντομα καλά. -

Απορία: σε τι χρειάζεται η πυξίδα; Μιλάμε για Dob πάντα, τα ρομποτικά έχουν πυξίδες εσωτερικά όταν έχουν το σύστημα Level North. Αλλά και ο μεταλλικός σωλήνας, ειδικά όταν είναι επιμήκης, επιδρά αρνητικά στις πυξίδες. Το Meade MySky μου αποσυντονίζεται και από τα κάγκελα του μπαλκονιού, ή από τα σίδερα της οικοδομής ακόμη.

-

Πωλείται Meade Focal reducer f/6.3

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της Ifikratis σε Μικρές Αγγελίες - Αρχείο

Ιφικράτη, όταν λες αναβάθμιση τι εννοείς; Υπάρχουν καλύτεροι μειωτές για SCT; (για τα διοπτρικά το ξέρω πως υπάρχουν). -

Με "μπρίζωσες" τώρα. Έλεγα να τυπώσω αυτοκόλλητα, αλλά τα μαγνητάκια είναι καλύτερα, καθώς δεν αφήνουν υπόλειμμα και είναι χρήσιμα για την στερέωση των χαρτών. Βέβαια σε μένα οι μεταλλικές επιφάνειες είναι μικρότερες και οι χάρτες είναι βιβλία ή πλαστικοποιημένοι, αλλά ένα λογότυπο δεν θα ήταν άσχημο, ακόμη και για λόγους ιδιοποίησης, είτε διακοσμητικούς. Η διαφάνεια είναι αυτή που κολλούσαμε στα εξώφυλλα των βιβλίων του σχολείου;

-

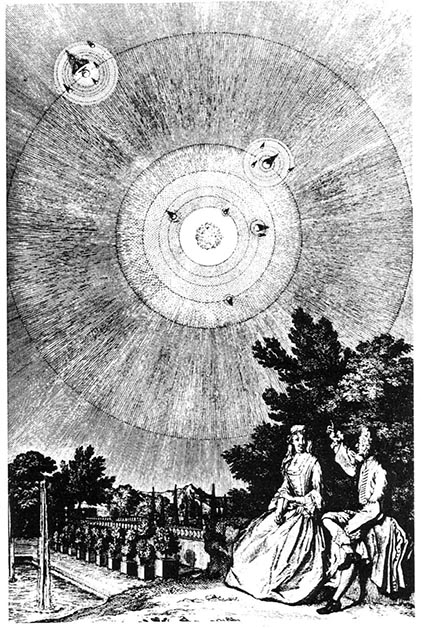

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

Distances, William Stanley Braithwaite, 1878-1962 Just where that star above Shines with a cold, dispassionate smile -- If in the flesh I'd travel there, How many, many a mile! If this, my soul, should be Unprisoned from its earthly bond, Time could not count its markless flight Beyond that star, beyond! -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Εσύ έχεις δίκιο. Δεν υπάρχει σώμα που να μην περιστρέφεται γύρω από τον εαυτό του. Ακόμη και ο ήλιος περιστρέφεται.

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

-

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις

To the Moon, John Brainard, 1796-1828 Bless thy bright face! though often blessed before By raving maniac and by pensive fool; One would say something more-- but who as yet, When looking at thee in the deep blue sky, Could tell the poorest thought that struck his heart? Yet all have tried, and all have tried in vain. At thee, poor planet, is the first attempt That the young rhymster ventures. And the sigh The boyish lover heaves, is at the Moon. Bards, who -- ere Milton sung or Shakspeare played The dirge of sorrow, or the song of love, Bards, who had higher soared than Fesole, Knew better of the Moon. 'T was there they found Vain thoughts, lost hopes, and fancy's happy dreams, And all sweet sounds, such as have fled afar From waking discords, and from daylight jars. There Ariosto puts the widow's weeds When she, new wedded, smiles abroad again, And there the sad maid's innocence -- 't is there That broken vows and empty promises, All good intentions, with no answering deed To anchor them on the substantial earth, Are shrewdly packed. -- And could he think that thou, So bright, so pure of aspect, so serene, Art the mere storehouse of our faults and crimes? I'd rather think as puling rhymsters think, O; love-sick maidens fancy -- Yea, prefer The dairy notion that thou art but cheese, Green cheese --than thus misdoubt thy honest face. -

Το σύμπαν της τέχνης και οι τέχνες τ' ουρανού

kkokkolis απάντησε στην συζήτηση του/της kkokkolis σε Λοιπές Αστρονομικές Συζητήσεις